UNDERSTANDING CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE – PART 3

UNDERSTANDING CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE – PART 3

“Cardiovascular disease kills one Australian every 12 minutes.”

THE PROBLEM

According to the World Health Organisation, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the world’s leading cause of death.2

Over 3 million Australians suffer from cardiovascular disease, and despite significant advances in the treatment of CVD it remains the cause of more deaths than any other disease in Australia.

It is also the most expensive disease in Australia— costing billions of dollars each year.3

WHAT IS CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE?

CVD describes a range of illnesses that involve the heart (cardiac) and blood vessels (vascular).

WHAT CAUSES CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE?

ATHEROSCLEROSIS

The main cause of CVD is atherosclerosis—the build up ofplaque inside the blood vessel walls.

Plaque consists of cholesterol, fat, and macrophages (a type of white blood cell).

Other substances like calcium may also be present.

The vessels become narrow or even completely blocked up, so little or no blood can travel through to the brain, heart and other organs.

The narrower the artery, the greater the risk of them being blocked by a rupture in the plaque-lined artery wall or a blood clot.

About 10% of heart attacks result from blockages directly related to the accumulated hard plaques.

The greater risks—and those leading to as many as 90% of heart attacks—are those of softer plaques, deposits of which are linked to higher cholesterol and are more unstable so more likely to rupture and block blood flow to the heart muscle or brain.6

These dangerous soft plaques often go unnoticed, even in angiograms.

We’re born with clean and flexible arteries that have the capacity to stay that way over time.

However a very early study observed that most of the young people studied, who were around 20 years old, had plaque deposits taking up 20% of the internal space in their blood vessels (the arterial lumen).7

Typically, by the time many of us are 45 years of age, plaque can have grown to the point that it narrows our arterial lumen by 50% or more in many people. And by 70 years of age, many live with up to 90% narrowing of some of their arteries, leaving only 10% opening for blood to flow through.7

But how does atherosclerosis happen? It’s a process with many contributing factors.

Inflammation

HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE

In addition to the processes causing atherosclerosis, high blood pressure (or hypertension) is a well-recognised, major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, contributing to half of all heart disease and strokes.17

REDUCING TO YOUR RISK

Most of the contributing factors to CVD are lifestyle elements, over which we have control.

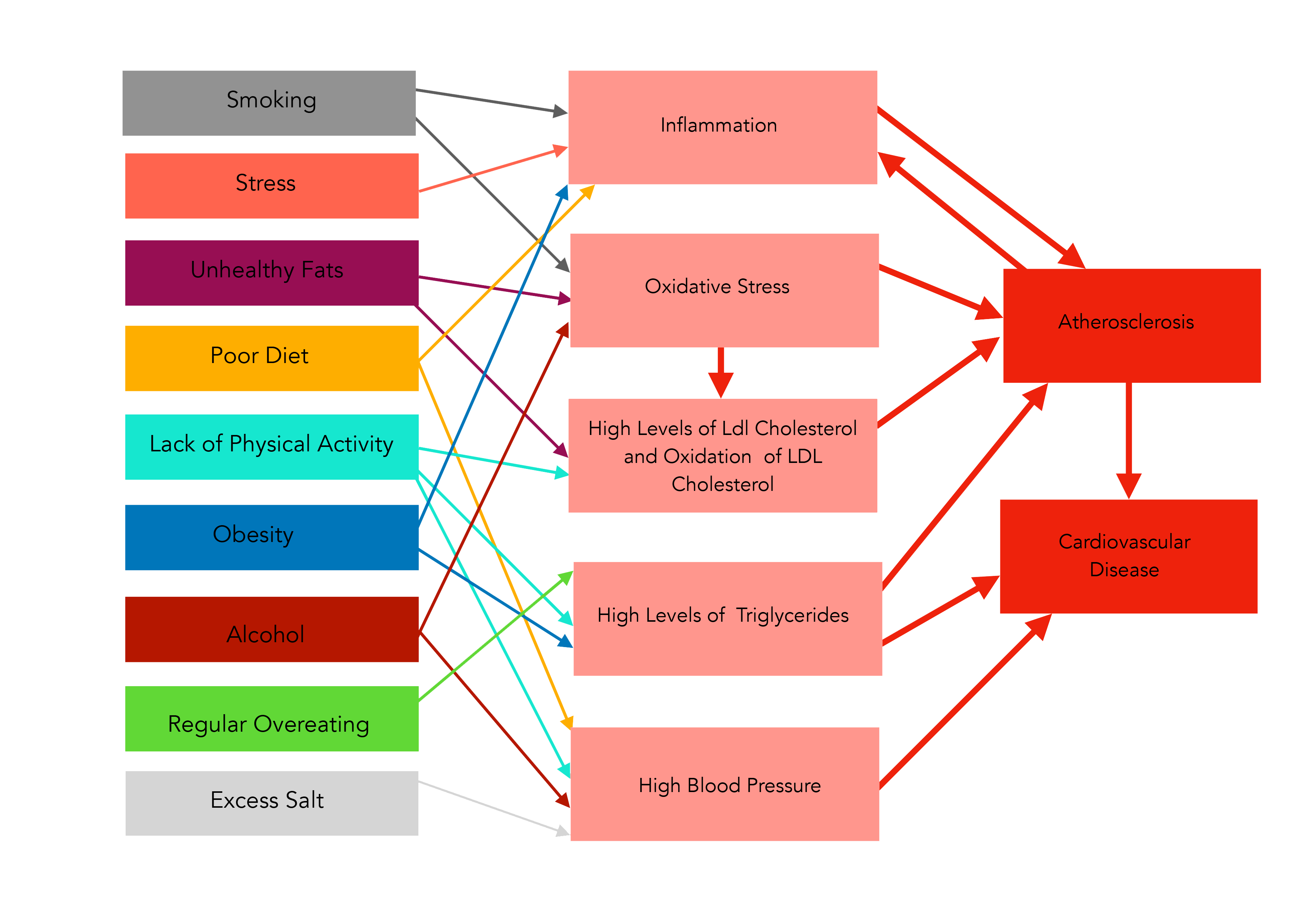

Many of these behaviours contribute in multiple ways to the development of CVD, as you can see from the tangled web of arrows in the diagram on pages 8 and 9.

To reduce the risk of CVD, individuals and populations need to deal with the contributing lifestyle factors.

SMOKING

Smoking is a major contributor to both inflammation and oxidative stress—two of the key elements of the atherosclerosis process. According to the Heart Foundation of Australia, there is overwhelming medical and scientific evidence that smoking promotes coronary heart disease18,19 and is a major cause of stroke20,21. The more you smoke the greater your risk. But even smoking just one to four cigarettes a day can double or triple coronary risk.22 Further, scientific evidence has established that exposure to second-hand smoke increases the risk of coronary heart disease by 25-30% in non-smokers.23,24 Quitting smoking, or never starting in the first place, is a huge step in reducing cardiovascular risk both for yourself and for those around you.13

UNHEALTHY FATS

The third key element in the atherosclerosis process is the oxidation of high levels of LDL cholesterol in our blood stream. Reducing LDL levels has a major impact on cardiovascular risk, and may be achieved by limiting saturated and trans fats in our diet.25 Processed foods and foods of animal origin are the major sources of trans and saturated fats. In contrast, a whole food, plant-based diet contains little of these bad fats, but moderate to low amounts of good fats—found in foods like nuts, seeds, and avocados. Additionally, reducing these bad fats in our diets will also reduce the chance that the LDL cholesterol in our blood will be oxidised.

OVERALL POOR DIET

Nutritious whole food plant-based diets contain high levels of grains, fruits, and vegetables. These foods provide our bodies with fibre, vitamins and minerals, anti-oxidants, and polyphenols—all of which act in a variety of ways to protect against inflammation, oxidation and atherosclerosis.26,27 A diet low in these nutritious foods and high in fats, salt and sugars, contributes to the atherosclerosis pathways while providing little or no protection against them.

LACK OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Research has shown that exercise protects against CVD in a number of ways. Firstly, it can be effective in raising HDL (good) cholesterol levels while reducing LDL (bad) cholesterol levels.28 It can also increase our anti-oxidant capacity, thereby reducing the risk of LDL (bad) cholesterol being oxidised.29 Exercise can reduce high blood pressure—a major CVD risk factor—and strengthen your heart and cardiovascular system, resulting in improved circulation. Importantly, exercise can reduce body fat and help you maintain a healthy body weight.30,31

OBESITY

Research has shown that unnecessary weight gain worsens all elements of your cardiovascular risk profile, including unhealthy levels of blood fats (such as LDL cholesterol and triglycerides) and hypertension, with obese individuals five times more likely to suffer from hypertension.32,33

The greater a person’s fatness, the worse their cardiovascular risk factors become.34,35

Body fat around the abdomen has the greatest impact on cardiovascular risk, and repeated weight fluctuations—from frequently losing weight then regaining it—cause plaque formation to accelerate.36,37

Maintaining a healthy body weight throughout adult life, or taking steps to achieve successful long term weight loss, represent a significant way of reducing a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease.38

ALCOHOL

Research appears to give a slightly confusing picture when it comes to the impact of alcohol on cardiovascular disease, but the information becomes clearer when it is carefully assessed.

What is known is that regular consumption of alcohol increases blood pressure, and that around 15% of hypertension—a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease—is due to drinking alcohol.39

What is also known is that the current state of research does not allow us to say unequivocally that alcohol protects against heart disease. It might do this in some people, but it definitely doesn’t in many groups.

According to the Heart Foundation of Australia, alcohol can damage your heart, and at-risk individuals should not drink alcohol at all.40

Furthermore, any protective effect that does exist has quite likely been exaggerated due to other diet and lifestyle factors not being taken into account.

Any presumed cardiovascular benefits from drinking alcohol need to be carefully weighed against the tendency of alcohol to elevate blood pressure, not to mention the many other adverse health consequences.39

According to the American Heart Association, most of the professed cardiovascular benefits of drinking alcohol can be achieved through diet and exercise, and people who do not already drink alcohol should not start drinking.41,42

Good Salt Bad Salt?

You may have heard the suggestion that some salt is bad and some salt is good.

The argument proposes that table salt purchased in supermarkets has been stripped of its true nutrient content, bleached, and polluted with toxic chemicals and anti-caking agents.

The argument then points to pure rock salt from the sea or the mountains that has been hand-harvested and washed.

It is available to purchase in its pure, nutritious state, ready to provide us with a healthy version of sodium— a nutrient essential to human health.

Although this viewpoint approaches the topic a little differently, the conclusions its proponents draw are largely the same—eat less processed food with its high salt levels, and eat more unprocessed whole foods to obtain the right amounts of both sodium and potassium.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Extensive scientific research has been conducted in an effort to curtail the western world’s biggest killer—cardiovascular disease. And while some of the finer details are sometimes disputed (a healthy and necessary part of good science), there is overwhelming evidence of the benefits of key behaviours:

REFERENCES

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of Death 2011

(3303.0). In: Statistics ABo, ed. Canberra2013 • 2. World

Heath Organisation. The Top Ten Causes of Death2007 •

3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cardiovascular Disease: Australian Facts 2011. 2012; http://www.aihw.gov.au/ publication-detail/?id=10737418510. Accessed December, 2012 • 4. Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A Tale of Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(1):54-63 • 5. Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, et al. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the european society of cardiology working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. European Heart Journal. January 1, 2008 2008;29(2):270-276 • 6. Forrester JS, Shah PK. Lipid Lowering Versus Revascularization: An Idea Whose Time (For Testing) Has Come*. Circulation. August 19, 1997 1997;96(4):1360-1362 •

7. General findings of the International Atherosclerosis Project. Lab Invest. May 1968;18(5):498-502 •

8. Lamon BD, Hajjar DP. Inflammation at the molecular interface of atherogenesis: an anthropological journey. Am J Pathol. Nov 2008;173(5):1253-1264 •

9. Kondo T, Hirose M, Kageyama K. Roles of oxidative stress and redox regulation in atherosclerosis. J Atheroscler Thromb. Oct 2009;16(5):532-538 •

10. Pitocco D, Tesauro M, Ales- sandro R, Ghirlanda G, Cardillo C. Oxidative stress in diabetes: implications for vascular and other complications. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(11):21525-21550 •

11. Kulshreshtha A, Goyal A, Veledar E, et al. Association Between Ideal Cardiovascular Health and Carotid Intima‚ÄêMedia Thickness: A Twin Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. February 21, 2014 2014;3(1) •

12. Badimon L, Vilahur G. LDL-cholesterol versus HDL-cholesterol in the atherosclerotic plaque: inflammatory resolution versus thrombotic chaos. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Apr 2012;1254:18-32 •

13. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Nguyen TH, et al. Effect of plant ster- ols in combination with other cholesterol-lowering foods. Metabo- lism. Jan 2008;57(1):130-139

• 14. Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Schnohr P, Jensen GB, Benn M. Nonfasting triglycerides, cholesterol, and ischemic stroke in the general popu- lation. Ann Neurol. Apr 2011;69(4):628-634

• 15. Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Nonfasting triglycer- ides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA. Jul 18 2007;298(3):299-308

• 16. Weber C, Noels H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1410-1422 • 17. Guo X, Zhang X, Guo L, et al. Association Between Pre-hypertension and Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta- analysis of Prospective Studies. Curr Hypertens Rep. Nov 15 2013 • 18. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. Jun 26 2004;328(7455):1519

• 19. Enstrom JE, Kabat GC. Envi- ronmental tobacco smoke and coronary heart disease mortality in the United States–a meta-analysis and critique. Inhal Toxicol. Mar 2006;18(3):199-210

• 20. Hankey GJ. Smoking and risk of stroke. J Cardiovasc Risk. Aug 1999;6(4):207-211 • 21. Yamagishi K, Iso H, Kitamura A, et al. Smoking raises the risk of total and ischemic strokes in hypertensive men. Hypertens Res. Mar 2003;26(3):209- 217 •

22. Bjartveit K, Tverdal A. Health consequences of smoking 1-4 cigarettes per day. Tob Control. Oct 2005;14(5):315-320.

3. Villablanca AC, McDonald JM, Rutledge JC. Smoking and rdiovascular disease. Clin Chest Med. Mar 2000;21(1):159-172 • 24. Steenland K. Passive smoking and the risk of heart disease. JAMA. Jan 1 1992;267(1):94-99 • 25. Judd JT, Clevidence BA, Muesing RA, Wittes J, Sunkin ME, Podczasy JJ. Dietary trans fatty acids: effects on plasma lipids and lipoproteins of healthy men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. Apr 1994;59(4):861-868 • 26. Davis N, Katz S, Wylie-Rosett J. The effect of diet on endothelial function. Cardiol Rev. Mar-Apr 2007;15(2):62-66 • 27. Kahleova H, Matoulek M, Malinska H, et al. Vegetarian diet improves insulin resistance and oxidative stress markers more than conventional diet in subjects with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. May 2011;28(5):549-559 •

28. Myers J. Exercise and Cardiovascular Health. Circulation. January 7, 2003 2003;107(1):e2-e5 • 29. Kasapis C, Thompson PD. The effects of physical activity on serum C-reactive protein

and inflammatory markers: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. May 17 2005;45(10):1563-1569 • 30. Woolf K, Reese CE, Mason MP, Beaird LC, Tudor-Locke C, Vaughan LA. Physical activity is as- sociated with risk factors for chronic disease across adult women’s

life cycle. J Am Diet Assoc. Jun 2008;108(6):948-959 •

31. Gilliat- Wimberly M, Manore MM, Woolf K, Swan PD, Carroll SS. Effects of habitual physical activity on the resting metabolic rates and body compositions of women aged 35 to 50 years. J Am Diet Assoc. Oct 2001;101(10):1181-1188 •

32. Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lan- cet. Oct 1 2005;366(9492):1197-1209 •

33. Wolf HK, Tuomilehto J, Kuulasmaa K, et al. Blood pressure levels in the 41 populations of the WHO MONICA Project. J Hum Hypertens. Nov 1997;11(11):733-742 • 34. Reaven GM. Insulin resistance: the link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Med Clin North Am. Sep 2011;95(5):875-892 • 35. Liberato SC, Maple-Brown L, Bressan J, Hills AP. The relation- ships between body composition and cardiovascular risk factors

in young Australian men. Nutr J. 2013;12:108 •

36. Kannel WB, D’Agostino RB, Cobb JL. Effect of weight on cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. Mar 1996;63(3 Suppl):419S-422S

37. Elbassuoni E. Better association of waist circumference with insulin resistance and some cardiovascular risk factors than body mass index. Endocr Regul. Jan 2013;47(1):3-14 •

38. Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Sullivan

L, Parise H, Kannel WB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med. Sep 9 2002;162(16):1867-1872 • 39. Puddey IB, Beilin LJ. Alcohol is bad for blood pressure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. Sep 2006;33(9):847-852 •

40. National Heart Foundation of Australia. Cardiovascular Conditions. 2012; http://www.heartfoundation. org.au/yourheart/cardiovascular conditions/Pages/heart-failure. aspx •

41. Lucas DL, Brown RA, Wassef M, Giles TD. Alcohol and the cardiovascular system: research challenges and opportunities.

J Am Coll Cardiol. Jun 21 2005;45(12):1916-1924 •

42. O’Keefe JH, Bybee KA, Lavie CJ. Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health: The Razor-Sharp Double-Edged Sword. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50(11):1009-1014 •

43. Du S, Neiman A, Batis C, et al. Understanding the patterns and trends of sodium intake, potassium intake, and sodium to potassium ratio and their effect on hypertension in China. Am J Clin Nutr. Nov 20 2013 •

44. Aburto NJ, Hanson S, Gutierrez H, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2013;346:f1378 •

45. Cook NR, Obarzanek E, Cutler JA, et al. Joint effects of sodium and potassium intake on subsequent cardiovascular disease: the Trials of Hypertension Prevention follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. Jan 1 2009;169(1):32-40.