Essentials of Choosing Healthy Food – PART 2

Essentials of Choosing Healthy Food – PART 2

Good food tastes delicious, adds pleasure to life and helps us celebrate important social occasions.

Most importantly it gives us the energy and nutrients to stay alive and to truly thrive.

What you eat can help you stay healthy and feel great!

Healthy eating also plays an important role in maintaining your body’s health and preventing diseases such as heart disease, diabetes and some cancers.1

They say “You are what you eat”—so what is good nutrition?

And how does choosing to eat healthy foods really make a difference to our lives?

WHY IS HEALTHY EATING IMPORTANT?

Eating a well balanced diet can:1

Recommended dietary guidelines2

What should I be eating?

The key to good eating is to enjoy a variety of nutritious foods from each of the five food groups and drink plenty of water.

For many, healthy eating does not come naturally.

It takes planning and preparation.

Use the information below to help solidify your healthy eating plans.

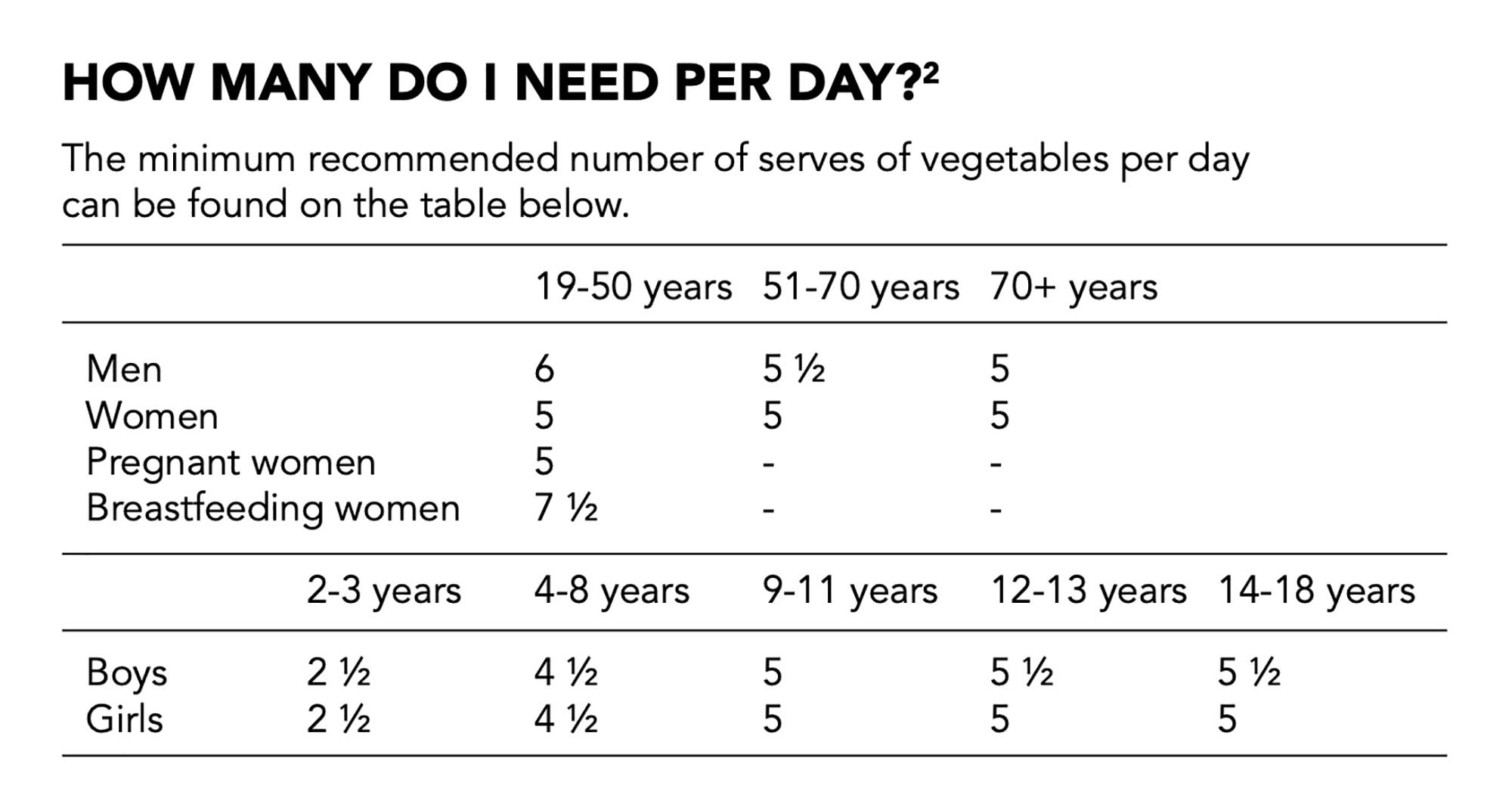

Vegetables, legumes and beans

Most of us know that vegetables, legumes, and beans are good for us, so why is it that 90% of us don’t eat enough vegetables?4

In 2009/10, Australian households spent an average of $237 a week on food and beverages.

Of this, about $63 was spent on food prepared outside the home (restaurants and takeaways), and $32 a week on alcoholic drinks.

Meat, fish and seafood collectively accounted for $30 a week on average.5

The foods we choose are influenced by many factors such as price, availability, culture, personal preferences, and health and nutrition concerns.

Vegetables are cost effective as they provide a high level of nutrients for generally very low kilojoules.

They provide an array of vitamins, minerals, dietary fibre and phytonutrients (nutrients naturally present in plants).4 Different vegetables, legumes, and beans contribute in different ways, making variety crucial to good health.6

Choosing different colours is one way to do this, so make sure your plate has at least three different coloured vegetables every day.

Eating a mixture of fresh salads and cooked vegetables is good for a healthy boost in vitamins and anti-oxidants.7

Cooked vegetables make certain nutrients easier for the body to absorb.

For example, beta-carotene and lycopene are better absorbed from cooked carrots and tomatoes than when raw.

In fact, adding some olive oil during cooking can further improve their biological availability; but remember to not heat the olive oil beyond its smoke point.1

Remember to maximise your nutrition from cooked vegetables by cooking them until just tender, don’t keep them warm for long periods of time and use minimal water.

Legumes (also known as pulses) are beans, peas and lentils, and can be found dried, canned, cooked or frozen.

Examples include soya beans, red kidney beans, chickpeas, red lentils, mung beans, peanuts or split peas.

There is consistent evidence from population health (epidemiological) studies that shows that eating legumes can play a role in reducing the risk of chronic disease, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and becoming overweight, as well as improving gut health.8

They are nutritional powerhouses filled with phytochemicals (class of natural mollecules with multiple health benefits) and dietary fibre.

Legumes are low in fat and contain a source of B vitamins, as well as a range of minerals including calcium, potassium, phosphorus and magnesium.

They are a source of energy giving carbohydrates, with a low glycemic index rating.

Legumes are also low in sodium and naturally gluten-free (great for those with coeliac disease or gluten intolerance).9,10

What is a Standard Serve?2,11

Choosing different colours is one way to do this, so make sure your plate has at least three different coloured vegetables every day.

Eating a mixture of fresh salads and cooked vegetables is good for a healthy boost in vitamins and anti-oxidants.12

Cooked vegetables make certain nutrients easier for the body to absorb.

For example, beta-carotene and lycopene are better absorbed from cooked carrots and tomatoes than when raw.

In fact, adding some olive oil during cooking can further improve their biological availability; but remember to not heat the olive oil beyond its smoke point.1

Remember to maximise your nutrition from cooked vegetables by cooking them until just tender, don’t keep them warm for long periods of time and use minimal water.

Legumes (also known as pulses) are beans, peas and lentils, and can be found dried, canned, cooked or frozen.

There is consistent evidence from population health (epidemiological) studies that shows that eating legumes can play a role in reducing the risk of chronic disease, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and becoming overweight, as well as improving gut health.13

They are nutritional powerhouses filled with phytochemicals (class of natural mollecules with multiple health benefits) and dietary fibre.

Legumes are low in fat and contain a source of B vitamins, as well as a range of minerals including calcium, potassium, phosphorus and magnesium.

They are a source of energy giving carbohydrates, with a low glycemic index rating.

Legumes are also low in sodium and naturally gluten-free (great for those with coeliac disease or gluten intolerance).14,15

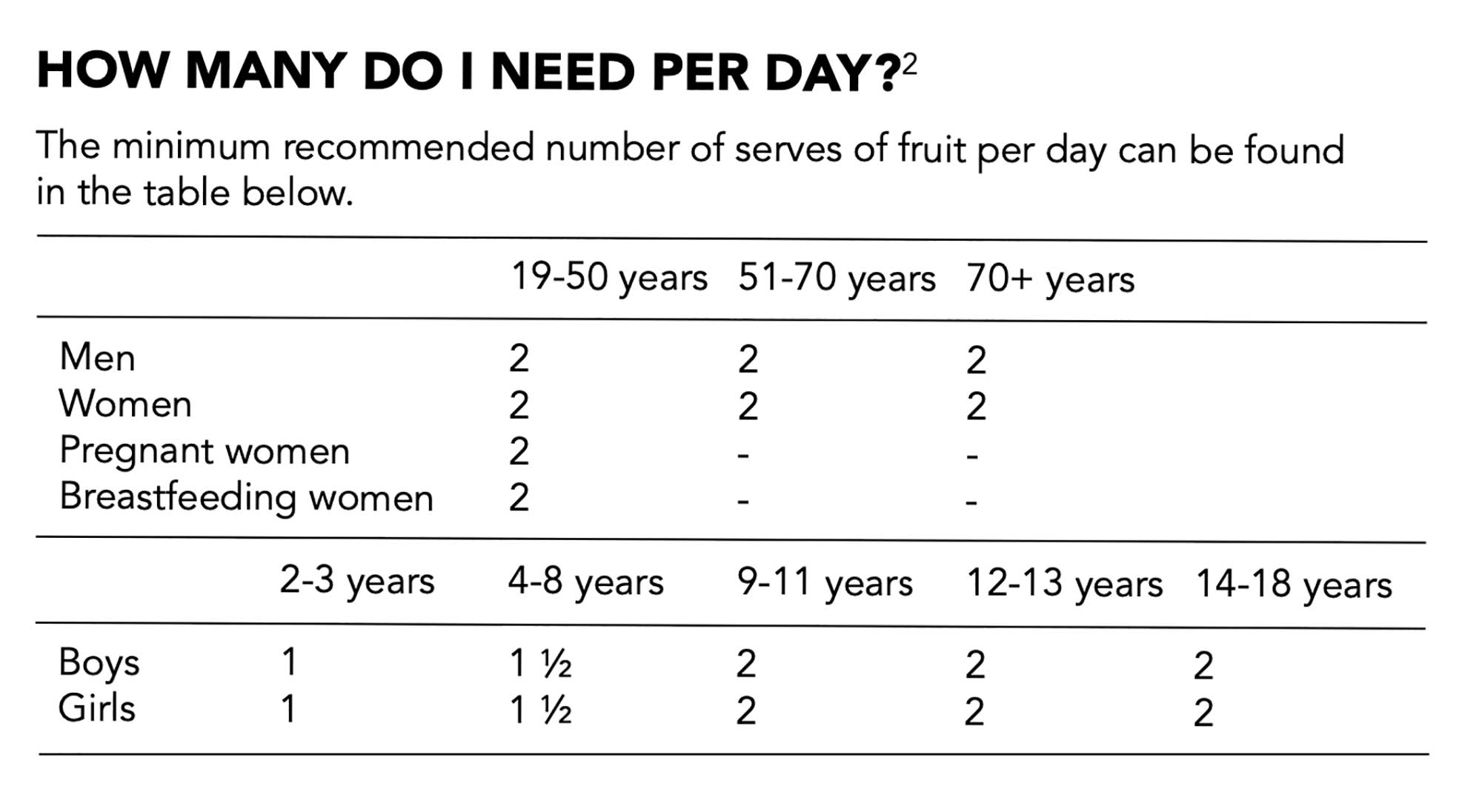

FRUIT

Most Australians eat only half the recommended quantity of fruit.5

However, many of us prefer to drink our fruit in the form of fruit juice.

This unfortunately comes with more sugar and less fibre.

It is a concentrated source of energy, so is not ideal for weight management.

It is much easier to drink a glass of orange juice (freshly squeezed) than it is to eat the four fresh oranges that went into making that juice!

Despite recent trends in fruit being labelled a baddie in terms of sugar content, it is a natural and nutritious food.

It contains little fat, and again is packed with vitamins, minerals, anti-oxidants and fibre.16

Dried fruit is also a healthy choice.

However, it is a concentrated source of energy (with water being removed in the drying process) and should be included in moderation.

FRUIT

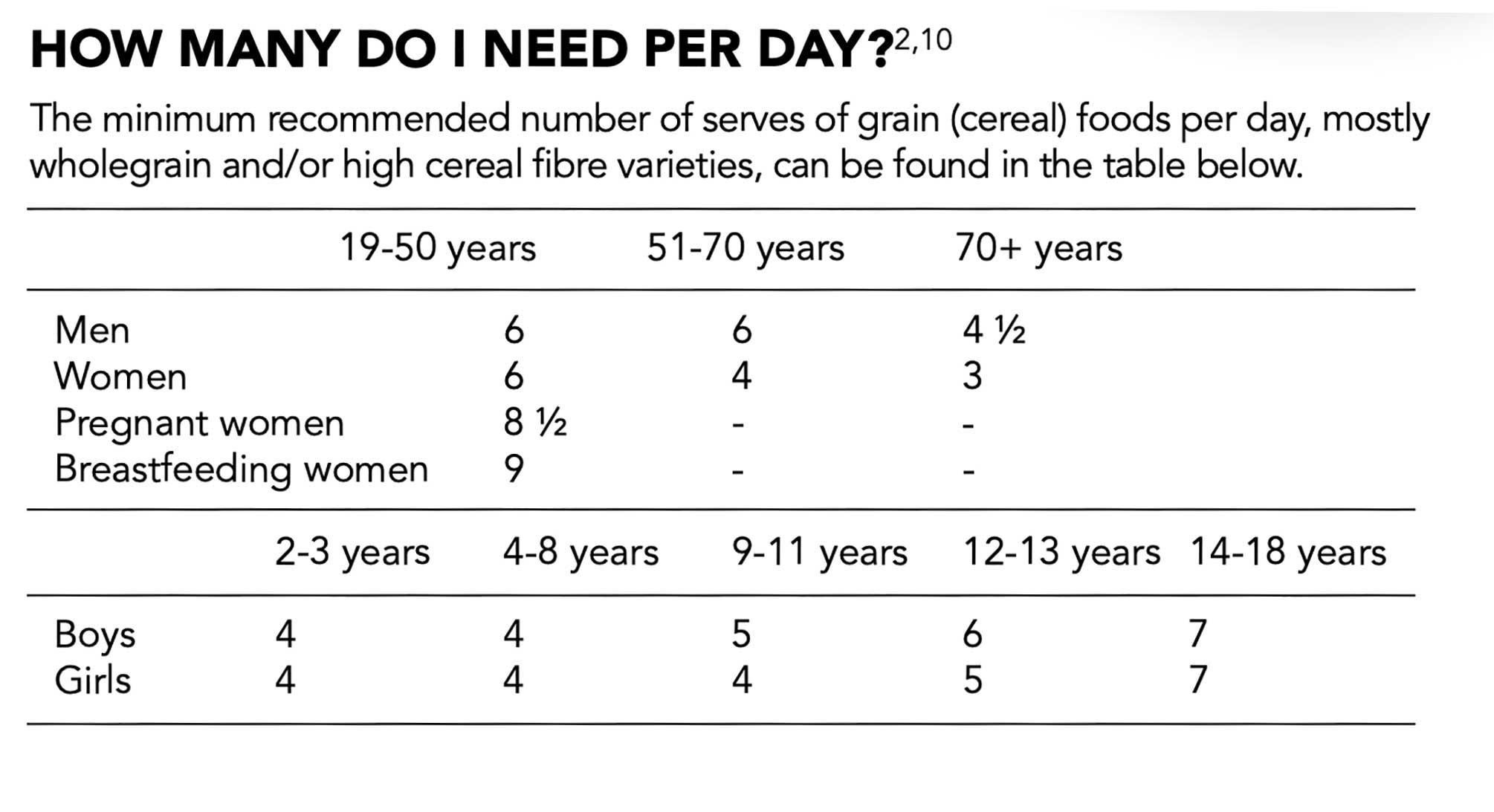

There are a wide variety of grains available which are important for health. Grain foods include wheat, oats, rice, corn, barley, sorghum, rye, millet, amaranth, buckwheat and quinoa.17

Each of these grains provides a network of nutritional properties including high carbohydrate, low fat, a good source of protein and varying amounts of vitamins, minerals, fibre and glycemic load.

Grain-based foods make an important contribution to your nutrient intake.

There is more and more emerging evidence supporting not only the role of grains in a healthy diet, but particular links with grains (specifically wholegrains) and disease protection.18-23

Most Australians consume less than half the recommended quantity of wholegrain foods, but eat too much refined grain (cereal) foods. At least two-thirds of our choices should be wholegrain varieties.2

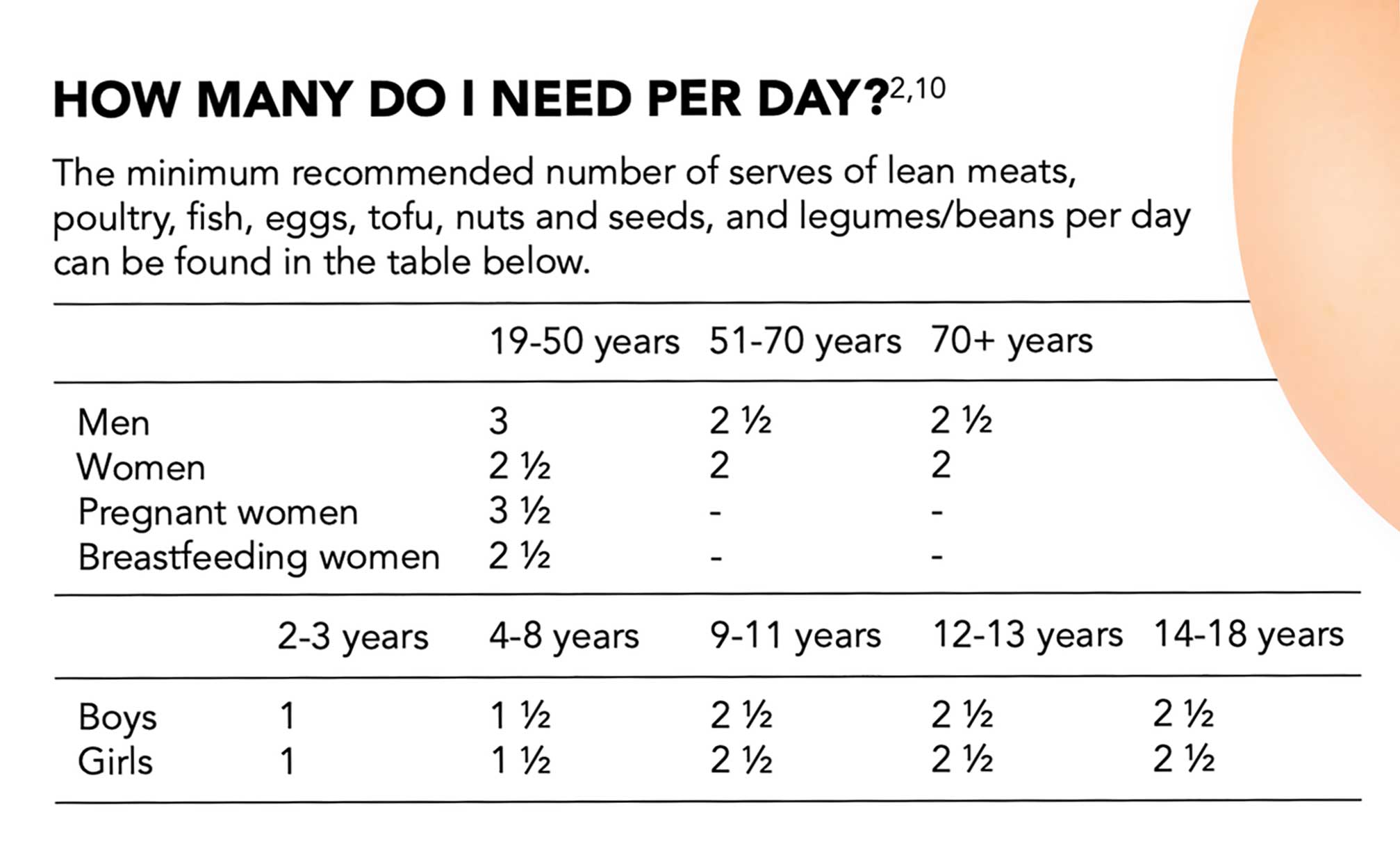

Lean meat, poultry, fish,eggs and/or plant based alternatives

Eating a variety of foods from this group provides many nutrients, including protein, iron, zinc and other minerals and vitamins (particularly those of the vitamin B group).

Vitamin B12 is found mainly in animal-based products.23

Lean red meat is high in iron and can be an important food, especially for some groups including women (particularly when pregnant)24 and athletes.

However, regular consumption of larger quantities of red meat may be associated with increased risk of colorectal (bowel) cancer.25

In fact, the World Cancer Research Fund states that “red or processed meats are convincing or probable causes of some cancers.”26

Fish is low in saturated fat and high in unsaturated fat and a rich source of iodine.27

Fish, particularly oily fish such as salmon and tuna, can be a valuable source of essential omega-3 fatty acids.

Consumption has been linked with reducing the risk of many chronic diseases and various disorders such as poor eyesight, inflammation, dementia, cardiovascular disease, depression and diabetes.28-30

Eggs provide a low cost source of protein and other nutrients, and are quick and easy to prepare.31

Alternatives to animal foods, including nuts, seeds, legumes, beans and tofu, can provide a valuable, affordable source of protein and other nutrients that are found in meat.

There is increasing evidence that consuming protein from plant rather than animal sources may in fact be one of the reasons why vegetarians generally have a lower risk of being overweight, obese or experiencing chronic disease.32

Including nuts as a regular component of your diet is recommended, and has been linked with regulating inflammatory processes,32 improved glycemic control,33 weight maintenance,32 and cholesterol lowering properties.34

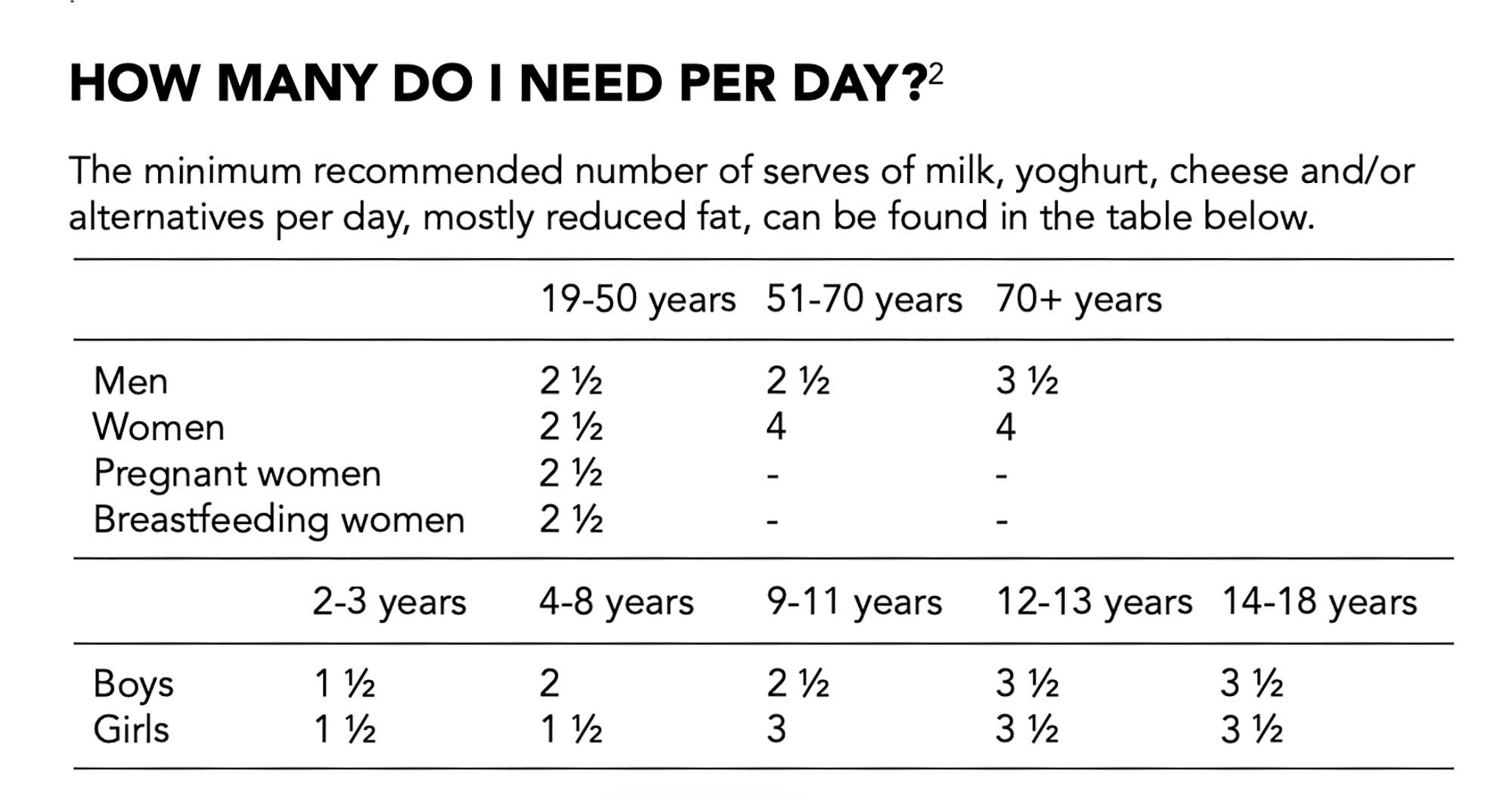

Dairy and alternatives

Dairy foods such as milk, yoghurt and cheese are well known for their calcium content.

However, they also contain significant amounts of other essential nutrients such as vitamins A and B12, riboflavin, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium and zinc.35

Remember to choose reduced fat and/or reduced salt varieties where possible.36

Foods such as canned fish eaten with the bones (e.g. salmon), fortified soy milk, green leafy vegetables, nuts such as almonds, tofu, cereals and legumes can also be rich sources of calcium.

Sesame seeds and sesame paste (tahini) have also been shown to be rich sources of calcium, particularly in vegetarians.37

What about other or extra food?

Some foods such as lollies, crisps, biscuits, soft drinks, takeaway, chocolate etc., do not fit into the main food groups.

They are not essential to provide the nutrients your body needs and some contain excessive additional fat, salt and sugars.

These extra foods can add to the enjoyment of a healthy diet, but should only be chosen sometimes or in small amounts.

REFERENCES

1. Saxelby C. Nutrition for Life. 5th ed. Victoria: Hardie Grant Books; 2006.

2. National Health & Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines: Summary Report. 2013; http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/n55.

3.The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. (2015). Breastfeeding. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 44(1), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12530

4. Department of Health. Victoria, A. (2020, July 23). Food Safety. Department of Health. Victoria, Australia. Retrieved July 26, 2022, from https://www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/your-guide-to-food-safety)

5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Food and Nutrition 2012: in brief. Canberra: Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare;2012.

6. Liu RH. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am J Clin Nutr. Sep 2003;78(3 Suppl):517S-520S.

7. Johns T, Eyzaguirre PB. Linking biodiversity, diet and health in policy and practice. Proc Nutr Soc. May 2006;65(2):182-189.

8. Kaur C, Kapoor HC. Antioxidants in fruits and vegetables – the millennium’s health. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 2001;36(7):703-725.

9. Flock MR, Kris-Etherton PM. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010: implications for cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. Dec 2011;13(6):499-507.

10. Grains and Legumes Nutrition Council. Legumes and Health. http://www.glnc.org.au/legumes/legumes-health/

11. Cabrera C, Lloris F, Gimenez R, Olalla M, Lopez MC. Mineral content in legumes and nuts: contribution to the Spanish dietary intake. Sci Total Environ. Jun 1 2003;308(1-3):1-14.

12. Pollard CM, Nicolson C, Pulker CE, Binns CW. Translating government policy into recipes for success! Nutrition criteria promoting fruits and vegetables. J Nutr Educ Behav. May-Jun 2009;41(3):218-226.

13. Slavin JL, Lloyd B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv Nutr. Jul 2012;3(4):506-516.

14. Flight I, Clifton P. Cereal grains and legumes in the prevention of coronary heart disease and stroke: a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Nutr. Oct 2006;60(10):1145-1159.

15. Djousse L, Driver JA, Gaziano JM. Relation between modifiable lifestyle factors and lifetime risk of heart failure. JAMA. Jul 22 2009;302(4):394-400.

16. Grains and Legumes Nutrition Council. Grains and Nutrition, Grains and Health. http://www.glnc. org.au/grains/grains-and-health/

17. He M, van Dam RM, Rimm E, Hu FB, Qi L. Whole-grain, cereal fiber, bran, and germ intake and the risks of all-cause and cardiovascular disease specific mortality among women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. May 25 2010;121(20):2162-2168.

18. Flint AJ, Hu FB, Glynn RJ, et al. Whole grains and incident hypertension in men. Am J Clin Nutr. Sep 2009;90(3):493-498.

19. Jonnalagadda SS, Harnack L, Liu RH, et al. Putting the whole grain puzzle together: health benefits associated with whole grains–summary of American Society for Nutrition 2010 Satellite Symposium. J Nutr. May 2011;141(5):1011S-1022S.

20. McKeown NM, Troy LM, Jacques PF, Hoffmann U, O’Donnell CJ, Fox CS. Whole- and refined-grain intakes are differentially associated with abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adiposity in healthy adults: the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. Nov 2010;92(5):1165-1171.

21. Balci YI, Ergin A, Karabulut A, Polat A, Dogan M, Kucuktasci K. Serum Vitamin B12 and Folate Concentrations and the Effect of the Mediterranean Diet on Vulnerable Populations. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. Oct 2 2013.

22. Simpson JL, Bailey LB, Pietrzik K, Shane B, Holzgreve W. Micronutrients and women of reproductive potential: required dietary intake and consequences of dietary deficiency or excess. Part II–vitamin D, vitamin A, iron, zinc, iodine, essential fatty acids. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. Jan 2011;24(1):1-24.

23. Kim E, Coelho D, Blachier F. Review of the association between meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. Nutr Res. Dec 2013;33(12):983-994.

24. Wiseman M. The second World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research expert report. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Proc Nutr Soc. Aug 2008;67(3):253-256.

25. Food Standards Australia New Zealand Consumer Information: Mercury in Fish 2011; http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumerinformation/mercuryinfish.cfm. Accessed March, 2013.

26. Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. JAMA patient page. Eating fish: health benefits and risks. JAMA. Oct 18 2006;296(15):1926.

27. Raatz SK, Silverstein JT, Jahns L, Picklo MJ. Issues of fish consumption for cardiovascular disease risk reduction. Nutrients. Apr 2013;5(4):1081-1097.

28. Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: new recommendations from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. Feb 1 2003;23(2):151-152.

29. Applegate E. Introduction: nutritional and functional roles of eggs in the diet. J Am Coll Nutr. Oct 2000;19(5 Suppl):495S-498S.

30. Marsh KA, Munn EA, Baines SK. Protein and Vegetarian Diets. Medical Journal of Australia Open. 2012;1(2):7-10.

31. Gopinath B, Buyken AE, Flood VM, Empson M, Rochtchina E, Mitchell P. Consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids, fish, and nuts and risk of inflammatory disease mortality. Am J Clin Nutr. May 2011;93(5):1073-1079.

32. Li SC, Liu YH, Liu JF, Chang WH, Chen CM, Chen CY. Almond consumption improved glycemic control and lipid profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. Apr 2011;60(4):474-479.

33. Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Nut consumption, weight gain and obesity: Epidemiological evidence. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Jun 2011;21 Suppl 1:S40-45.

34. Damasceno NR, Perez-Heras A, Serra M, et al. Crossover study of diets enriched with virgin olive oil, walnuts or almonds. Effects on lipids and other cardiovascular risk markers. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Jun 2011;21 Suppl 1:S14-20.

35. Parker CE, Vivian WJ, Oddy WH, Beilin LJ, Mori TA, O’Sullivan TA. Changes in dairy food and nutrient intakes in Australian adolescents. Nutrients. Dec 2012;4(12):1794-1811.

36. Kai SH, Bongard V, Simon C, et al. Low-fat and high-fat dairy products are differently related to blood lipids and cardiovascular risk score. Eur J Prev

Cardiol. Sep 3 2013.

37. Reid MA, Marsh KA, Zeuschner CL, Saunders AV, Baines SK. Meeting the nutrient reference values on a vegetarian diet. Medical Journal of Australia Open. 2012;1(2):33-40.