KEYS TO EMOTIONAL HEALTH- PART 12

KEYS TO EMTIONAL HEALTH – PART 12

STRESSED OUT

Stress is a natural human response to pressure when faced with challenging, and sometimes dangerous situations.1

A stress free life however, is not the goal!

Stress is helpful when it increases our ability to be alert, energised, switched on and resourceful in managing daily tasks.

Stress becomes detrimental when it leaves us feeling fatigued, tense, anxious, burnt out or overwhelmed.

Everyone has a different response threshold to stress, and sometimes our thresholds can vary depending on what’s happening in our lives. When stress is unusually prolonged or repetitive, it becomes a potential threat to health.2

This is known as distress.

In 2011-12, 70.1% of Australians aged 18 years and over experienced a low level of psychological distress.

Around one in ten adults (10.8%, or 1.8 million people) experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress.3

How does diSTRESS affect our Health?

HEART HEALTH

Stress causes a release of adrenaline, a hormone which increases our heart rate and causes our blood vessels to constrict, which in turn increases blood pressure.4

It has also been shown to increase the thickness of our blood as well as clotting properties.5

GUT FUNCTION

Heartburn, nausea, indigestion, vomiting, diarrhoea and constipation can be implicated as a result of stress.6

IMMUNE FUNCTION

The concept that our psychological state can affect our nervous system, that in turn affects our immune system, is an established science.7

When people feel greater fear or distress prior to surgery, poorer outcomes including longer stays, complications and rehospitalisation are more likely to occur.8

EMOTIONAL HEALTH

Stress changes the way we feel, and this can influence our behaviour and decisions.

These behaviours and choices can include poorer nutrition choices, less physical activity and poorer sleep habits.9,10

Less Stress11

Not everyone stresses to the same extent about the same things.

More often than not, stress is a combination of circumstances, personality and past experience.

Some may feel as though there is nothing you can do about stress.

The fact of the matter is, more often than not, your career and family responsibilities will always be there, the bills won’t stop, and you can only fit 24 hours in a day.

In order to gain back some control in your life, use some of the following steps and strategies for better managing stress.

IDENTIFY THE SOURCE OF STRESS IN YOUR LIFE

Sources of stress aren’t always obvious, and it can be very easy to overlook your own thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that promote stress.

HOW? Start a stress journal, determine responsibility.

REFLECT ON HOW YOU CURRENTLY COPE WITH STRESS

Are your strategies healthy or unhealthy, counterproductive or effective?

HOW? Make healthier lifestyle changes using Booklet 1—Living Well as your guide.

Remember, start with small and sustainable goals for long term success.

AVOID UNNECESSARY STRESS

Of course not all stress can be ignored, and it is definitely not a good idea to avoid something that needs to be addressed.

However, there may be some you can better manage.

HOW? Learn to say no, take time out, avoid stress aggrevators, take control of your environment, prioritise your to-do list for the day, and complete the musts rather than the shoulds.

ALTER THE SITUATION

If you can’t avoid a situation, what tools and strategies can you put in place to ensure it doesn’t happen again?

HOW? Communicate with others, express your thoughts, employ better time management practices.

ADAPT TO THE STRESSOR

Sometimes changing your own thoughts and attitudes can help manage stress.

HOW? Think positively, adjust standards, put everything in perspective.

Stress benefits of exercise12

HOW TO MEND YOUR MIND

More and more research is being conducted on the links between diet, exercise, rest and mindset in helping people to fix how they feel. Here are five major strategies:

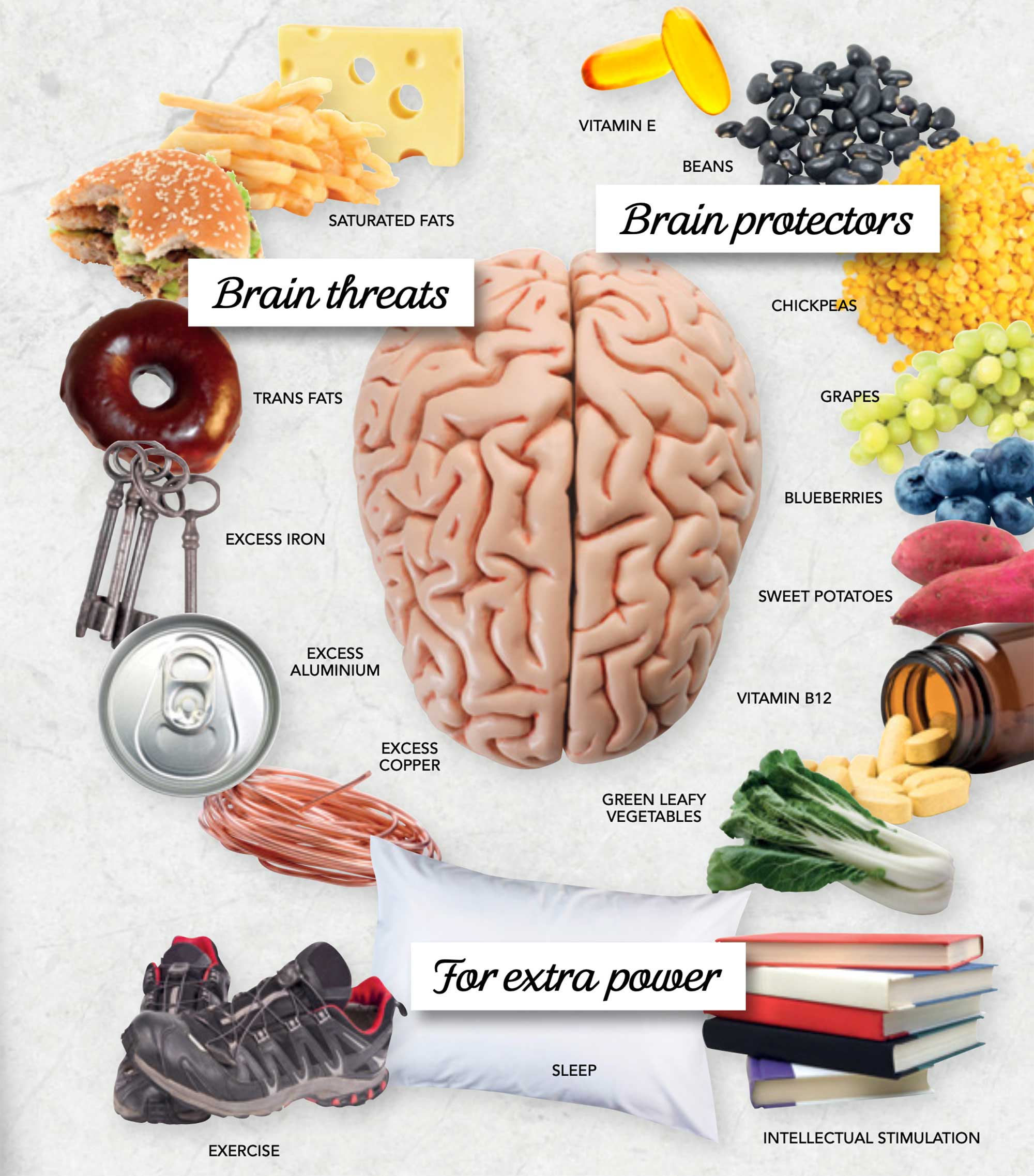

1. EAT BRAIN FOODS

When it comes to feeling great, a whole-food plant-based diet comes out on top.

A liberal supply of fruits, vegetables and grains provides the best nourishment for your brain.13

Although there is hardly a poor choice among them, the standout contenders include:

BERRIES contain phytonutrients that boost cognition, coordination and memory.14

CRUCIFEROUS VEGETABLES such as broccoli and cauliflower can help enhance memory.15

GARLIC phytonutrients may help prevent dementia including Alzheimer’s disease.16

GREEN LEAFY VEGETABLES such as spinach and kale help support the immune system and keep an ageing brain sharp.17,18 They are also high in iron and a rich source of folate.19

NUTS consumption may enhance mood,20 and can help with clarity and clear thinking.

OLIVE OIL is rich in phytochemicals that help enhance blood flow in the brain.21

POMEGRANATE can help with brain and memory protection due to high anti-oxidant levels.22

SEEDS such as sunflower, sesame, flax and chia contain high vitamin E and omega-3 beneficial fats, as well as minerals and phytochemicals that may help brainpower and mood.23,24

TOMATOES which are rich in lycopene that possess potent anti-oxidant properties that may help fight the development of dementia.25

WHOLEGRAINS rich in phytonutrients and B group vitamin,25-27 are a great energy source needed for maintaining concentration throughout the day and improving memory.

There are some foods that you should be cautious and aware of that act as brain drainers.

Foods and substances such as sugar,28 alcohol,29 nicotine,30 as well as high fat diets,28 have been known to hinder brain function. In addition, high carbohydrate meals loaded with refined food, sugar or junk can decrease mental performance.31

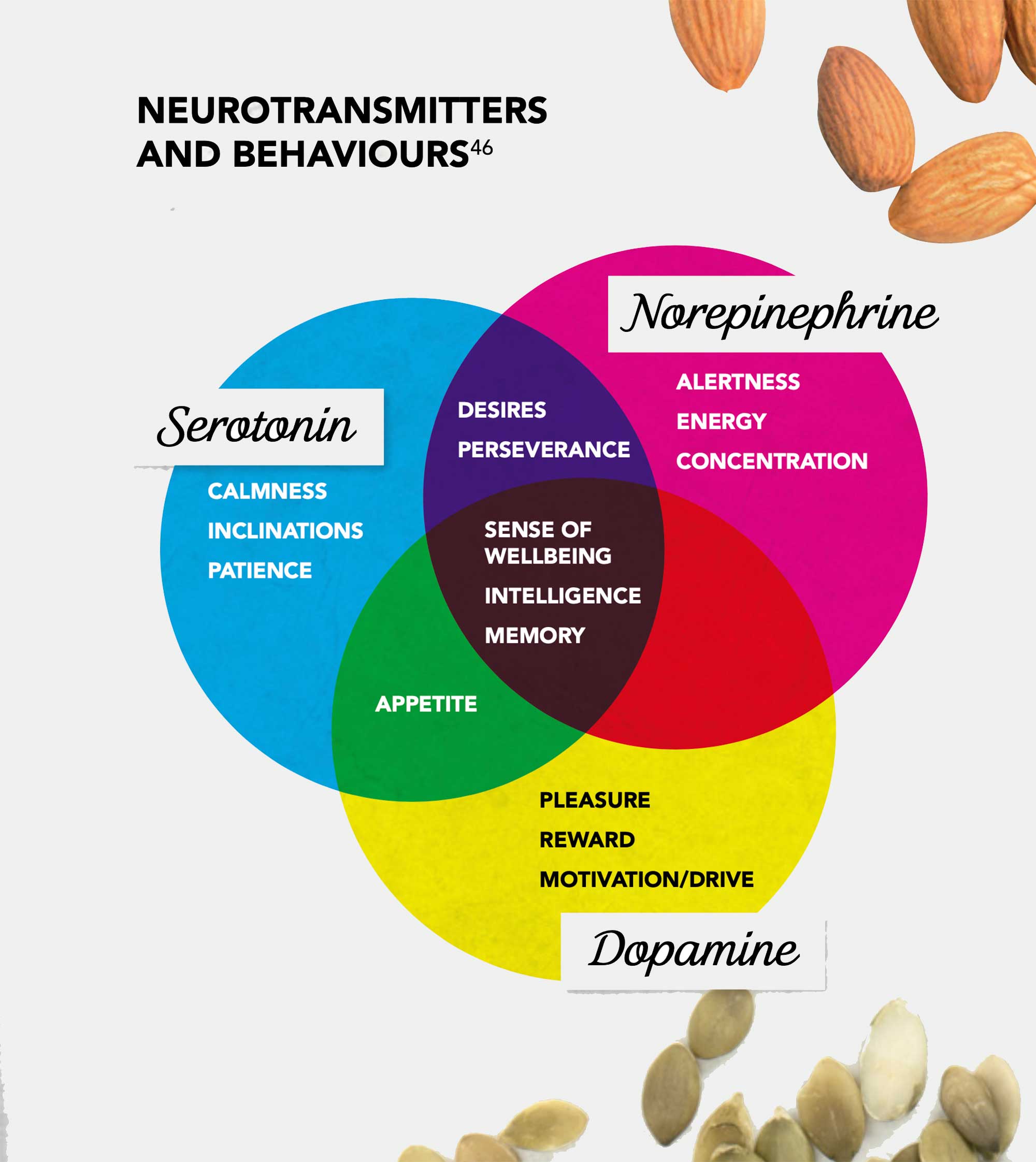

Neurotransmitters are chemicals released in the brain that affect our anxiety and moods.

See diagram on the opposite page to understand how the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine affect our behaviours.

Tryptophan is an amino acid which helps produce serotonin, and tyrosine is another amino acid that is linked to norepinephrine and dopamine.

Good food sources of these include pumpkin and chia seeds, seaweed, lentils, nuts, eggs, tofu and sun-dried tomatoes.19,32-36

OMEGA-3 is a vital nutrient for mind health. In fact, deficiency is one of the most common contributing factors to mental deteriation and illness.37

It is an effective memory booster,38 and important for cognitive performance.39

Foods high in omega-3 include fish (salmon, herring, trout, mackerel, tuna), flax seeds, chia seeds, walnuts, canola oil and green soybeans.19,40

2. MOVE MORE

Exercise is a powerful way to mend the mind.

Exercise and its effects have been linked to relieving depression and reducing anxiety.41,42

It has also been known to enhance cognition,43 memory and brain development.44,45

So what are you waiting for?

It is never too late to begin an exercise regime.

The benefits of exercise go far beyond emotional health. See Booklet 8—Less is More for more information.

3. GO GREEN

Getting out into nature is another useful strategy.

Go on, give it a try. It is easy in a modern world to feel a disconnect with the environment, yet there is something incredibly therapeutic about immersing yourself in the natural world.

Hospital patients with a view of natural landscape have shorter hospital stays.47

Exposure to nature can help enhance relationships and promote positive health behaviours.

Breathing in fresh unpolluted air, as well as safe exposure to sunlight, can also help elevate health and mood.48

4. REST WELL

Sleep has a huge effect on our emotional and mental health.

Lack of adequate sleep affects mood,49 motivation,50 judgement,51 and our perception of events.52

Lack of sleep can also be associated with anxiety disorders and depression.53,54

Try avoiding caffeine, alcohol and nicotine.

Try sticking to a sleep schedule, using natural light,55 establishing a pre-sleep routine,56,57 and preparing light evening meals to improve the quality of your sleep.58

See Booklet 9—Water & Sleep for more information.

5. THINK POSITIVE

REFERENCES

1. Mason JW. A historical view of the stress field. Journal of Human Stress. 1975;1(2):22-36 concl •

2. Bosch JA, De Geus EJC, Kelder A, Veerman ECI, Hoogstraten J, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Differential effects of active versus passive coping on secretory immunity. Psychophysiology. 2001;38(5):836-846 •

3. Statistics ABo. Australian Health Survey: First Results, 2011-2012. http:// www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/1680ECA402368CCFCA25 7AC90015AA4E/$File/4364.0.55.001.pdf, 2013 •

4. Nestel PJ. Blood-pressure and catecholamine excretion after mental stress in labile hypertension. Lancet. 1969;1(7597):692-694 •

5. Jern C, Eriksson E, Tengborn L, Riberg B, Wadenvik H, Jern S. Changes of plasma coagulation and fibrinolysis in respone to mental stress. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 1989;62(2):767-771 •

6. Taché Y, Martinez V, Million M, Wang L. Stress and the gastrointestinal tract III. Stress-related alterations of gut motor function: Role of brain corticotropin-releasing factor receptors. American Journal of Physiology – Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2001;280(2 43-2):G173-G177 •

7. O’Leary A. Stress, emotion, and human immune function. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(3):363-382 •

8. Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Alley PG, Booth RJ. Psychological stress impairs early wound repair following surgery. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(5):865-869 •

9. Mouchacca J, Abbott GR, Ball K. Associations between psychological stress, eating, physical activity, sedentary behaviours and body weight among women: A longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1) •

10. Astill RG, Verhoeven D, Vijzelaar RL, Van Someren EJW. Chronic stress undermines the compensatory sleep efficiency increase in response to sleep restriction in adolescents. Journal of Sleep Research. 2013;22(4):373-379 •

11. Smith M, Seagal R. Stress Management: How to Reduce, Prevent, and Cope with Stress. http://www.helpguide.org/ mental/stress_management_relief_coping.htm. Accessed February, 2013 •

12. Penedo FJ, Dahn JR. Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. Mar 2005;18(2):189-193 •

13. Hughes TF, Andel R, Small BJ, et al. Midlife fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of dementia in later life in swedish twins. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18(5):413-420 •

14. Devore EE, Kang JH, Breteler MMB, Grodstein F. Dietary intakes of berries and flavonoids in relation to cognitive decline. Annals of Neurology. 2012;72(1):135-143 • 15. Kang JH, Ascherio A, Grodstein F. Fruit and vegetable consumption and cognitive decline in aging women. Annals of Neurology. 2005;57(5):713-720 •

16. Gupta VB, Indi SS, Rao KSJ. Garlic extract exhibits antiamyloidogenic activity on amyloid-beta fibrillogenesis: Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Phytotherapy Research. 2009;23(1):111-115 •

17. Joseph JA, Shukitt-Hale B, Denisova NA, et al. Long-term dietary strawberry, spinach, or vitamin E supplementation retards the onset of age-related neuronal signal-transduction and cognitive behavioral deficits. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18(19):8047-8055 •

18. Heo JC, Park CH, Lee HJ, Kim SO, Kim TH, Lee SH. Amelioration of asthmatic inflammation by an aqueous extract of Spinacia oleracea Linn. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2010;25(3):409-414 •

19. Zealand FSAaN. NUTTAB 2010. http:// www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/nutrientables/nuttab/ Pages/default.aspx •

20. Abbas G, Naqvi S, Erum S, Ahmed S, Atta Ur R, Dar A. Potential antidepressant activity of areca catechu nut via elevation of serotonin and noradrenaline in the hippocampus of rats. Phytotherapy Research. 2013;27(1):39-45 •

21. Rabiei Z, Bigdeli MR, Rasoulian B. Neuroprotection of dietary virgin olive oil on brain lipidomics during stroke. Current Neurovascular Research. 2013;10(3):231-237 • 22. Noda Y, Kaneyuki T, Mori A, Packer L. Antioxidant activities of pomegranate fruit extract and its anthocyanidins: Delphinidin, cyanidin, and pelargonidin. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(1):166-171 •

23. Sargi SC, Silva BC, Santos HMC, et al. Antioxidant capacity and chemical composition in seeds rich in omega-3: Chia, flax, and perilla. Food Science and Technology. 2013;33(3):541-548 •

24. Blomhoff R, Carlsen MH, Andersen LF, Jacobs Jr DR. Health benefits of nuts: Potential role of antioxidants. British Journal of Nutrition. 2006;96(SUPPL. 2):S52-S60 •

25. Guest J, Grant R, Garg M, Mori TA, Croft KD, Bilgin A. Changes in oxidative damage, inflammation and [NAD(H)] with age in cerebrospinal fluid and influence of carotenoids. Inaugural Future of Experimental Medicine Conference ~ Inflammation in Disease and Ageing. Sydney2014 •

26. Slavin J. Whole grains and human health. Nutrition Research Reviews. 2004;17(1):99-110 •

27. Liu RH. Whole grain phytochemicals and health. Journal of Cereal Science. 2007;46(3):207- 219 •

28. Francis HM, Stevenson RJ. Higher Reported Saturated Fat and Refined Sugar Intake Is Associated With Reduced Hippocampal-Dependent Memory and Sensitivity to Interoceptive Signals. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2011;125(6):943-955 •

29. Guest J, Grant R, Garg M, Mori TA, Croft KD. Changes in oxidative damage, inflammation and [NAD(H)] with age in cerebrospinal fluid Plos One. 2014;In Press • 30. Danielson K, Putt F, TrumanP, Kivell BM. The effects of nicotine and tobacco particulate matter on dopamine uptake in the rat brain. Synapse. 2014;68(2):45-60 • .

31. Ross AP, Bartness TJ, Mielke JG, Parent MB. A high fructose diet impairs spatial memory in male rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2009;92(3):410-416 32. Venkatachalan M, Sathe SK. Chemical composition of selected edible nut seeds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(13):4705-4714 •

33. Fleurence J. Seaweed proteins: Biochemical, nutritional aspects and potential uses. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 1999;10(1):25-28 •

34. El-Adawy TA, Taha KM. Characteristics and composition of different seed oils and flours. Food Chemistry. 2001;74(1):47-54 • 35. Comai S, Bertazzo A, Bailoni L, Zancato M, Costa CVL, Allegri G. Protein and non-protein (free and protein-bound) tryptophan in legume seeds. Food Chemistry. 2007;103(2):657-661 •

36. Ayerza R. Seed composition of two chia (Salvia hispanica L.) genotypes which differ in seed color. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture. 2013;25(7):495-500 •

37. Peet M, Murphy B, Shay J, Horrobin D. Depletion of omega-3 fatty acid levels in red blood cell membranes of depressive patients. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;43(5):315-319 • 38. Petursdottir AL, Farr SA, Morley JE, Banks WA, Skuladottir GV. Effect of dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on brain lipid fatty acid composition, learning ability, and memory of senescence-accelerated mouse. Journals of Gerontology – Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2008;63(11):1153-1160 •

39. Fontani G, Corradeschi F, Felici A, Alfatti F, Migliorini S, Lodi L. Cognitive and physiological effects of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in healthy subjects. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;35(11):691-699 • 40. Simopoulos AP. Omega-3 fatty acids in wild plants, nuts and seeds. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;11(SUPPL. 6):S163-S173 •

41. McWilliams LA, Asmundson GJG. Is there a negative association between anxiety sensitivity and arousal-increasing substances and activities? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2001;15(3):161-170 •

42. Danielsson L, Noras AM, Waern M, Carlsson J. Exercise in the treatment of major depression: A systematic review grading the quality of evidence. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2013;29(8):573-585 •

43. Chang YK, Tsai CL, Huang CC, Wang CC, Chu IH. Effects of acute resistance exercise on cognition in late middle-aged adults: General or specific cognitive improvement? Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2014;17(1):51-55 •

44. Marcelino TB, Longoni A, Kudo KY, et al. Evidences that maternal swimming exercise improves antioxidant defenses and induces mitochondrial biogenesis in the brain of young Wistar rats. Neuroscience. 2013;246:28-39 •

45. Dao AT, Zagaar MA, Levine AT, Salim S, Eriksen JL, Alkadhi KA. Treadmill exercise prevents learning and memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology. Current Alzheimer Research. 2013;10(5):507-515 • •

46. Nedley N. Nourish Your Brain. The Lost Art of Thinking: How to Improve Emotional Intelligence and Achieve Peak Mental Performance: Nedley Publishing; 2010:145-190 •

47. Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 1984;224(4647):417-419 •

48. Gladwell VF BD, Wood C, Sandercock GR, Barton JL. The great outdoors: how a green exercise environment can benefit all. Extreme Physiology & Medicine. 2013;2(3) • 49. Kaida K, Niki K. Total sleep deprivation decreases flow experience and mood status. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2014;10:19-25 •

50. Hanlon EC, Andrzejewski ME, Harder BK, Kelley AE, Benca RM. The effect of REM sleep deprivation on motivation for food reward. Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;163(1):58-69 •

51. Killgore WDS, Killgore DB, Day LM, Li C, Kamimori GH, Balkin TJ. The effects of 53 hours of sleep deprivation on moral judgment. Sleep. 2007;30(3):345-352 • 52. Fabbri M, Tonetti L, Martoni M, Natale V. Sleep and prospective memory. Biological Rhythm Research. 2014;45(1):115-120 •

53. Araghi MH, Jagielski A, Neira I, et al. The complex associations among sleep quality, anxiety-depression, and quality of life in patients with extreme obesity. Sleep. 2013;36(12):1859- 1865 •

54. Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1059-1068 • 55. Hood B, Bruck D, Kennedy G. Determinants of sleep quality in the healthy aged: The role of physical, psychological, circadian and naturalistic light variables. Age and Ageing. 2004;33(2):159- 165 •

56. Mindell JA, Telofski LS, Wiegand B, Kurtz ES. A nightly bedtime routine: Impact on sleep in young children and maternal mood. Sleep. 2009;32(5):599-606 •

57. Johnson JE. A comparative study of the bedtime routines and sleep of older adults. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1991;8(3):129-136 •

58. Smith AP, Maben A, Brockman P. The effects of caffeine and evening meals on sleep and performance, mood and cardiovascular functioning the following day. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1993;7(2):203-206 •

59. Fredrickson BL. The value of positive emotions. American Scientist. 2003;91(4):330-335.